Alex Watson is a researcher and genealogist, based in Glasgow, Scotland, I hope that you find this website informative, it is an ongoing project, based on the research that I started, in 2004, on behalf of my friend Patrick Joynson-Wreford, it will continue to be updated as more information becomes available.

Please get in touch if you want to ask questions or need some help, also if you have any information, stories, photographs, etc, that you want to share.

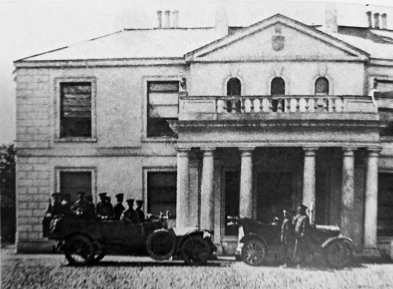

Seskinore House c.1880

'The old and picturesque McClintock mansion of Seskinore lies in the Parish of Clogherny (Cloichearnach, an offshoot of Clocher, Cloharach, or Cloithreach, meaning a stony place, and anglicised (Clogherny), near the village of Seskinore (called in a Map of the Plantation, Shaskanoure, 'pointing clearly,' says Joyce, 'Sescennodhar—ie, Grey Marsh,' about six miles south-east of Omagh, in the historic barony of that name.'

'Plantation Commissioners Divide Omagh Barony

When the Plantation Commissioners reached Tyrone they found that all the lands in the area belonged to the Crown except the Church lands and about 5,000 acres which had been granted by Queen Elizabeth to Sir Henry Oge O'Neill. These lands comprised the ancient Irish territory known as Mointerburn, and were the inheritance of Sir Phelim Roe O'Neill of Kinnaird, on the Blackwater.

Of the Undertakers among whom the precincts of Omagh was divided the principal recipient was George Tucket, Lord Audley, who was granted an estate of 3,000 acres; but this favourite of James I., having neglected to erect castles and settle British subjects on the lands, according to the articles of plantation. The grant ultimately reverted to the Crown.

'The Lord Audley,' reports Sir George Carew, twelve months after the division of the lands of the Omagh lands, “has not appeared, l nor any for him; nothing done.” His Lordship had come from Audley, in Staffordshire, and was the eighteenth Baron Tucket. His 3,000 acres in Omagh included 2,000 for himself and 1,000 for his wife, Elizabeth who was the daughter of Sir James Mervyn, of Fonthill, Gifford, Wiltshire.

He was created Earl Castlehaven in 1616 but only lived a few months afterwards.

When this property was sold after his death it was found that, besides the original 3,000 acres of meadow, 3,000 acres of pasture land, 2,000 acres of wood, 2,000 acres covered the bramble and furze, and 200 acres of bog, all of which had been thrown in gratuitously to his proportion as waste and unprofitable lands.

A considerable proportion of the lands so granted to Lord Castlehaven and sold after his death, fell to the possession of Sir Audley Mervyn, brother-in-law of Colonel Rory Maguire who married Deborah, daughter of Colonel Audley Mervyn, and relict of Sir Leonard Blennerhassett.'

The Weekly Irish Times, Saturday, January 20, 1940

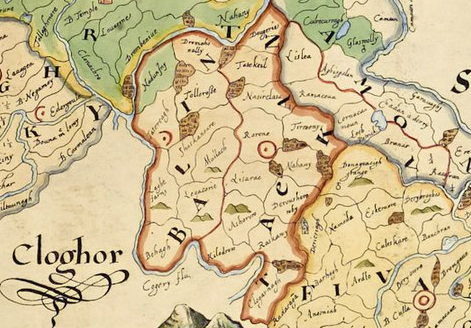

17th Century Barony Maps c.1609 - The Baronie of the Omey.

(From collection of maps of escheated counties of Ireland)

PRONI Ref: T1652/17

The Perrys are said to be of Welsh descent, the first of the name associated with the area is Thomas (d.c.1662), he was the father of James Perry Esq., of Ranelly who purchased the following:-

- On the 20th June 1662, Sir William Usher conveyed the lands of Ranelly to James Perry.

Memorandum of delivery of seizin of said lands:

On 4th July 1662 to said James Perry and on 25th January 1663 in consideration of £15 by said James Perry to his son George Perry And of Agreement dated 24th June 1662 that said Sir William Usher should not be bound to warrant the premises against any person to whom said Sir William Usher and others by deed dated 24th July 1634 had conveyed said premises to John Perry brother to said James Perry.

- On the 26th June 1662, Sir Audley Mervyn granted a fee farm of the lands of Moyloughmore, Mullorkmore or Mullaghmore to the same said 'James Perry, son of deceased Thomas Perry'.

James Perry of Ranelly (b. circa 1650) established his seat at Moyloughmore, which he named Perrymount. The estate was also historically known as Mullaghmore House and now stands in ruin. Unfortunately, little is known about James personally, including the name of his wife. However, records do identify the following sons:

-

Francis Perry, of Tityreagh near Omagh; married Elizabeth, fifth daughter of John Lowry of Ahenis (or Pomeroy) and Mary Buchanan, Co. Tyrone. He died without issue (dsp).

-

Samuel Perry; married first Catherine, eldest daughter of John Lowry of Ahenis (or Pomeroy) and Mary Buchanan (as above), by whom he had issue. He married secondly Isobel, only daughter of Hector Graham of Lee Castle, Queen's County, and Coolmaine House, Co. Monaghan. By her, he had:

-

Edward, a Captain in the Army

-

Catherine

-

-

George Perry, of whom presently.

Remains of Perrymount (2009).

George Perry, of Moyloughmore

Born circa 1700 – died circa 1774. He married Angel Sinclair, daughter of Rev. James Sinclair of Holyhill, near Strabane, and had issue:

-

Samuel Perry, of whom presently.

-

George Perry; married a daughter of Crawford, of Cooley, Co. Tyrone, and had issue: two sons and one daughter.

-

Margaret Perry; married her first cousin, Captain Edward Perry, son of Samuel Perry (above), and had issue: two daughters.

-

Letitia Perry; married — Johnston.

-

Adam Perry; married — Dick.

Samuel Perry, of Perrymount and Mullaghmore

Born circa 1730. He married a daughter of the Olphert family of Ballyconnell House, Co. Donegal, and had issue:

-

George Perry, of whom presently.

-

Mary Perry; married December 1781, Alexander McClintock, of Newtown, Co. Louth (b. 30 March 1746), nephew of Alexander McClintock of Drumcar (1692–1775). They had issue:

-

John McClintock, of Newtown, Co. Louth; died unmarried, 1845.

-

Samuel McClintock, heir to his uncle.

-

'To be sold by public cant at Mullaghmore in the County of Tyrone on Monday the fourteenth day of March inst.

All the household furniture which belonged to Samuel Perry, Esq., deceased, a considerable part of which has been but a short time in use; as also the farming utensils and stock of cattle belonging to the demesne of Mullaghmore, the stock consisting of several saddle and 'draft' horses, some extraordinary good milch cows, and other cattle. Six months credit will be given upon approved of security for every article above 20s. To be set also during the minority of the heir who is now about ten years of age, together or in parcels, and to be entered on immediately, the house offices and demesne of Mullaghmore; the house is large and in good order with stables coach-house and other offices, fit for the accommodation of a gentleman or farmer. The demesne consists of about eight plantation acres of arable and meadow ground, well enclosed into parks with quickest hedges in the high condition and well circumstanced as to firing, there being some hundred acres of turf bog in the farm; several acres are 'plowed' this season and any tenant that would take immediately may be accommodated at a reasonable value with turf hay and oats. It is situated about five miles from Omagh seven from Augher and three of Fintenagh good market towns to which the roads are very good. Proposals be received by Mr Samuel Galbraith of Greenmount near Omagh; a servant on the land will show the premises to any person inclined to take them.

All person to whom the said Samuel Perry was indebted are desired to furnish their accounts and the nature of their demands to the said Samuel Galbraith one of the executors, that they may be discharged and to enable the executors to do which, all persons who were indebted to the said Samuel Perry are desired immediately to pay such debts to the said Samuel Galbraith, Wybrants Olpherts or James Hamilton, Attorney, the executors or either of them.'

Extracts from the Londonderry Journal

4th March, 1774

The only son, George Perry of Perrymount and Moyloughmore, served as a Cornet of Horse. Born in 1762 and died in 1824, he married Mary, daughter of John Burgess. The couple had no surviving issue (d.s.p.). In his will, dated 15th May 1823, George devised his estate to his wife Mary for the duration of her life, and upon her death, to his nephew Samuel McClintock for life, with remainder to the first and other sons of Samuel McClintock in tail male, followed by various other remainders.

SESKINORE LODGE, SESKINORE, AND MULLAGHMORE.

Seskinore Lodge, the seat of Mrs. Perry, (relict of the late George Perry, Esq.) is part and parcel of the Seskinore estate, and comprehends a neat and fashionable lodge, a tastefully planted lawn, and about sixty Irish acres of a farm, well adapted to the growth of flax and corn crops, and to that of garden vegetables and ornamental trees. The demesne however lies low, and the prospect from the lodge is exclusively confined to the little beauties of the home view; in which the rose, the sweet William, and the sweet brier, seem to vie, which shall diffuse the larger proportion of its fragrance through the surrounding scene.

The ancient residence of this family, was at a place called Mullaghmore, (most likely the Irish name of the townland on which the old family house is situated) but denominated Perrymount, during their occupation of the place; and this with the beautiful village of Seskinore, erected by the Perry family, in the immediate neighbourhood of the lodge, are parts and parcels of the same property; but of the extent of this property, its natural history, or the names of the townlands composing it, beyond what has been just mentioned, we know nothing. Some who profess (what we do not) to have a deep and extensive acquaintance with the Irish language, maintain that Seskinore, or more properly Sheskinore, is a combination of two Irish words which (by a free translation) may be made to signify 'the rich or golden soil of thistles,' the thistle weed, when shooting up in large quantities being the sure indication of a rich and marrowy soil. Whether this be admissible as a free translation, or whether it diverges too far from the literal meaning of the parent root to come within the limits of a just literary licence, we presume not to say; but as the best that we could make out we give it, and let the reader who finds fault with our translation provide us with a better.

These various respectable features of the Perry property, stand within a short walk (perhaps an English mile or more) of the great coach road between Dublin and Derry, by Omagh, which is the post town to them, and from which they are about five Irish miles distant.

N.B. A school for the education of the Protestant children of the neighbourhood, has been established in or near the village of Seskinore, by Mrs. Perry, and when we passed through that country in 1830, it was well attended, and very satisfactorily conducted by Mr. Halcoo, a young man educated for this office by the Education Society, in Kildare- street, Dublin.

'Ireland in the Nineteenth Century, and Seventh of England's Dominion: Enriched with Copious Descriptions of the Resources of the Soil, and Seats and Scenery of the North West District'

By A. Atkinson. Esq.

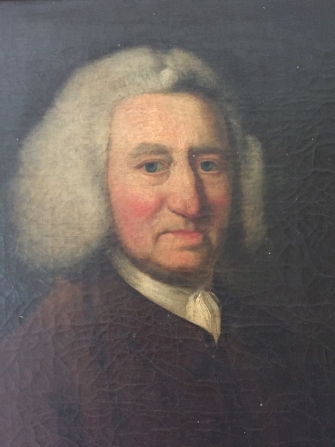

Alexander McClintock of Drumcar

(1692 - 1775)

Lease of 24 acre I.P.M. for one life or 31 years from 1 Nov., 1784. Rent: £21. 13s. 6d. p.a. George Perry, Perrymount, Co. Tyrone to Alexr. Moore, Seskinore, Co. Tyrone for Seskinore, Co. Tyrone

Seskinore, Drumconnolly and Tullyrush

- On 3rd July 1724 Henry Mervyn granted unto said Alexander McClintock said lands of Drumconnolly and Tullyrush with others therein described as. All that and those the towns and lands of Seskinore Drumconnolly and Tullyrush.

It has been suggested that Alexander McClintock of Drumcar bequeathed his Seskinore lands to his nephew; however, evidence indicates that he may have disposed of his holdings in County Tyrone prior to his death in 1775—or that his executors sold them thereafter.

- '1st July, 1783 To be sold by private contract the lands of Drumconnolly and Tulyrush containing 490 acres, a lease of lives renewal for ever, lying within three miles of Omagh and Fintona, both good market towns and on the Great Road from Dublin to Londonderry. The above lands are everywhere well accommodated with turf bog. Any gentleman purchaser who might be disposed to make it his residence and build a mansion house can have a bold and agreeable situation and a demesne of 100 acres now out of lease. For further particulars enquire of Mr Francis McFarland on the purchase. 5th July, 1783.'

(PRONI Reference : MIC60/4, Issues of the Londonderry Journal)

- 30th November 1785, a lease for part of Seskinore is recorded; Lease of 24 acre I.P.M. for one life or 31 years from 1 Nov., 1784. Rent: £21. 13s. 6d. p.a. George Perry, Perrymount, Co. Tyrone to Alexr. Moore, Seskinore, Co. Tyrone for Seskinore, Co. Tyrone

- 29th June 1791, a lease for part of Tullyrush is recorded;

Lease of 8 acre 3rd. I.P.M. for three lives or 31 years from 29 Sep., 1790. Rent: £18. 15s. p.a. George Perry, Perrymount, Co. Tyrone to Edward Delany, Tullyrush, Co. Tyrone for Tullyrush, Co. Tyrone.

(PRONI, D526/1/123, D526/1/119 etc).

Tullyheron Tullytemple and Rarone

18th November 1802 By Indenture made between Samuel Allen Hugh Hamilton therein described as trustees appointed by Will of James Hamilton deceased of the first part Jane Hamilton therein described as Widow of said James Hamilton of the second part James Hamilton therein described as Nephew and heir at law of said James Hamilton deceased of the third part and George Perry of the fourth part.

Reciting that said James Hamilton deceased being at time of his death seized in fee simple of the lands of Tullyheron Tullytemple and Rarone in the Barony of Omagh and County of Tyrone which lands of Tullytemple are a subdivision of said lands of Tullyheron did by his will devise said lands by the name of Tullyheron and Rarone to said Samuel Allen and Hugh Hamilton in trust to sell as therein And further reciting as therein.

It is Witnessed that in consideration of £3600 paid to said Samuel Allen and Hugh Hamilton and of 10/- a piece paid to Jane and James Hamilton said Samuel Allen Hugh Hamilton and James Hamilton according to their respective rights granted unto said George Perry the lands [including said lands fourthly mentioned at heading hereof]

Between 1805 and November 1811, lease records deposited at PRONI relating to the Perry lands at Seskanore consistently list George Perry as residing in Armagh. Two key leases from 1791 confirm that he had leased both a house and land near Armagh from his brother-in-law, John Henry Burgess, Esq., of Parkanaur, Co. Tyrone (PRONI, D1594/75).

In parallel, a set of 1805 lease documents for various bogland parcels (PRONI, D474/36–48), part of the estate of Rev. John Lowry, describe him as "Rev. John Lowry, Perrymount, Co. Tyrone", suggesting that he may have been residing at Perrymount during some of the period that George Perry was in Armagh.

By April 1812, leases begin to list George Perry as “of Seskanore,” which likely corresponds with the construction of Seskanore Lodge around this time.

Later, the Tyrone Constitution (1845) reports the arrival of Samuel McClintock at Seskanore, stating that the property had passed to him from his uncle, George Perry. Notably, no mention is made of Alexander McClintock of Drumcar, further reinforcing the conclusion that the inheritance came directly through the Perry line.

Omagh 60 Years ago.

FACTS ABOUT TOWN AND COUNTY.

[Extracts from files of “Tyrone Constitution”]

REJOICINGS AT SESKINORE.

SAMUEL M’CLINTOCK, ESQ.-

This estimable gentleman, to whom the Seskinore property (left him by his uncle, the late

George Perry. Esq.), has devolved on the death

of Mrs. Perry, visited Seskinore on Thursday

week: he was met a considerable way out of the

town by a joyous and delighted tenantry, who

took the horses from the carriage, and drew it to

the lodge amidst the most enthusiastic cheers.

Mr. M’Clintock spent some time at the house

of his relative, Mr. Sinclair Perry, Esq., and returned

by Balligawley same evening, but not before ordering abundance of refreshments for the congregated thousands. After night tar barrels blazed

in all directions, and an amateur band delighted

The people by the performance of several appropriate tunes. Mr M’Clintock was accompanied by his brother-in-law, Captain. Blake Knox,

and Counsellor Rutledge. From all we have

heard Mr. M’Clintock is well worthy the reception he met from a happy and respectable

tenantry. He is spoken of by all classes who

had the pleasure of his acquaintance in the

strongest terms. We hope soon to have the

gratification of hearing that he has come to

reside on the estate.- 'Tyrone Constitution'

18th April. 1845.

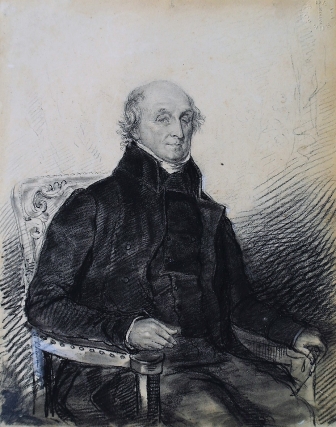

Above portrait: Alexander McClintock, Esq., of Newtown House, Co. Louth — nephew of Alexander McClintock of Drumcar, who was married to Mary Perry of Perrymount.

The McClintock family originated in Scotland and settled in Trinta, Co. Donegal, Ireland between 1597 and 1623.

-

Alexander McClintock, of Trinta, married in 1648 Agnes Stenson, daughter of Donald Maclean. He died on 6 September 1670.

-

Their son, John McClintock, born 1649, married Janet Lowry (daughter of John Lowry of Ahenis and Mary Buchanan) on 11 August 1687. He died in 1707 and had two notable sons:

-

Alexander McClintock, of Drumcar, Co. Louth (b. 1692), married Rebecca Sampson and died without issue in 1775.

-

John McClintock, of Trinta (b. 1698), married Susannah Maria Chambers, of Rock Hall. Their son:

-

Alexander McClintock, of Newtown, Co. Louth (b. 1746), married in 1781 Mary Perry, only daughter of Samuel Perry of Perrymount and Seskinore, Co. Tyrone. They had:

-

Samuel McClintock, of Newtown and Seskinore (b. 1790), JP for both counties, High Sheriff of Louth (1843), formerly a Lieutenant in the 18th Royal Irish Regiment. He married:

-

(1st) Jane Lane (d. 1837)

-

(2nd) in 1839, Dorothea (Dora) Knox, daughter of John Knox of Moyne Abbey. He died 13 December 1852, leaving two sons:

-

George Perry McClintock, b. 6 Nov 1819

-

Samuel John McClintock, d. 1856

-

-

-

-

-

-

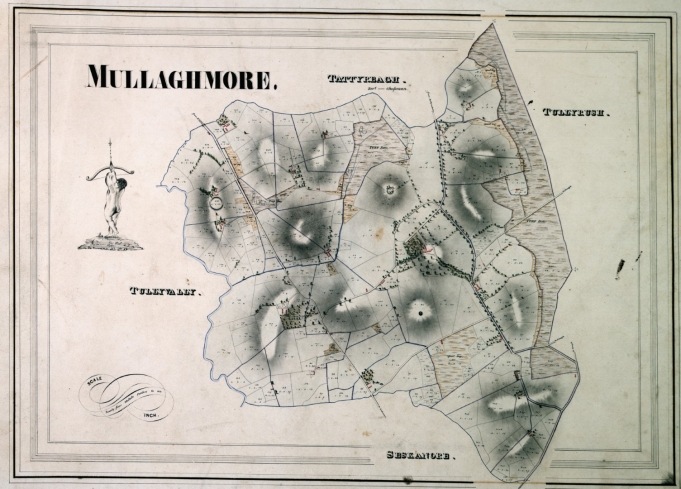

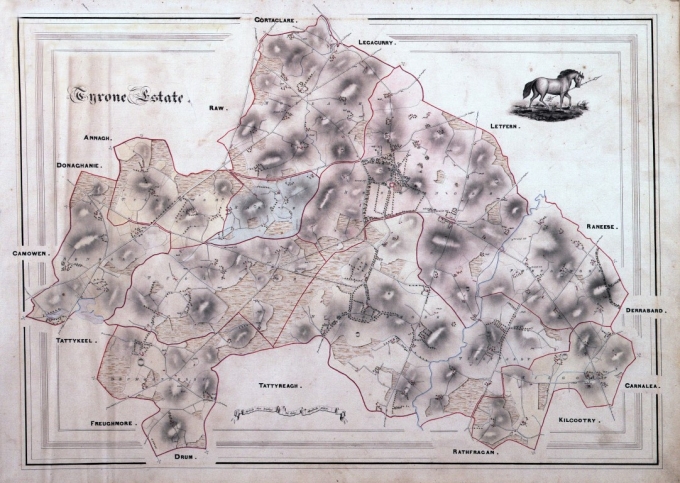

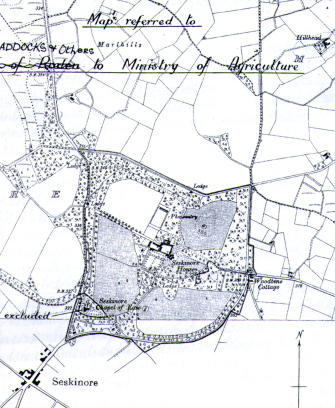

In 1845, following the death of Mary Perry, the estate passed to her nephew, Samuel McClintock. Upon taking possession, Samuel commissioned a full map of the estate in 1846, bound into a large red volume now held at PRONI (D586), providing the first comprehensive delineation of the Perry/McClintock estate.

'And reciting that by the order of the Court of Chancery in Ireland dated 17th June 1854. It was (amongst others) declared that under the will of said George Perry, the said George Perry McClintock was seized of an estate tail in possession of all the lands set forth”, “including the townlands of Drumconnelly [sic], Tullyrush, Tullyharm, Tullytemple, Rarone, Upper Mullaghmore, Lower Mullaghmore including the Mansion House and 10 acres, Moylagh, Ranelly, the mill at Ranelly and the town and lands of Seskanore all situate in the Barony of Omagh and the County of Tyrone and also the town and lands of Freighmore, Tullyvally and Kilgort situate in the Barony of Clogher and County of Tyrone and also the town and lands of Camowen situate in the Barony of East Omagh and said County of Tyrone and also the town and lands of Knockadreenan situate in the Barony of Armagh and County of Armagh', a total of 4553 acres.

Remains of Perrymount (Mullaghmore house) 2009.

An artist's rendering from 1862 depicts how Seskinore House would appear after its remodeling and extension, based on designs by the Londonderry and Belfast architectural firm Boyd & Batt (DB 4, 15 Mar, 1 Oct 1862, pp. 72, 254). The result was an impressive residence featuring five public rooms, ten bedrooms, dedicated staff quarters, and a separate house for the butler.

The McClintocks flourished at Seskinore, in contrast to many Irish landowners of the period who were often absent from their estates. The McClintocks, by contrast, resided on their land and maintained a strong local presence. The men of the family frequently pursued military careers.

Samuel McClintock married Dorothea (Dora) Knox, daughter of John Knox Esq. of Moyne Abbey, Co. Mayo, on 17 January 1839. The couple had two sons: George Perry McClintock, born 6 November 1839, and Samuel John McClintock, born in 1842, who died young on 1 September 1854.

Samuel McClintock passed away on 13 December 1852 at the age of 62. His wife Dora outlived him by 43 years, dying on 31 August 1896 aged 92. She was a beloved member of the family, known locally for her charitable nature and kindness.

Upon Samuel's death, the estate passed in tail male to their surviving son, Lieutenant Colonel George Perry McClintock, J.P., D.L., of the 4th Battalion, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. He served as Aide-de-Camp to two successive Lord Lieutenants of Ireland—the Duke of Abercorn and the Earl Spencer. On 1 May 1860, he married Amelia (Emy) Harriett Alexander, daughter of the Rev. Samuel Alexander of Termon, and Charlotte Frances Beresford. Charlotte was the daughter of the Rev. Charles Cobbe Beresford, Rector of Termon (1809–1850) and a connection of the Marquess of Waterford. Amelia's maternal grandmother was Amelia Montgomery, daughter of Sir William Montgomery of Magbiehill and Anne Evatt.

Dorothea McClintock nee Knox, wife of Samuel McClintock.

b.c. 1804 - d. 31st August 1896 aged 92.

Lt. Col. George Perry McClintock

Amelia (Emy) Harriett Alexander

(Above) Rev. Charles Cobbe Beresford and Amelia Montgomery, maternal grandparents of Amelia (Emy) Alexander, wife of George Perry McClintock.

A post-nuptial settlement, dated 8 November 1860, entailed the estate in tail male.

George and his wife had twelve children:

-

Beresford George Perry, b. 15 Feb 1861; dsp 31 Jan 1870.

-

John (Jack) Knox, of whom presently.

-

Harry Edward, b. 11 Oct 1865; dsp 2 Apr 1866.

-

Augustus, Captain and Brevet-Major, DSO, 1st Battery Seaforth Highlanders; served with the West African Frontier Force; 1st Class Resident, Bornu Province, Northern Nigeria (mentioned in despatches); d. 24 June 1912.

-

Leopold Arthur, late Captain, 3rd Battery Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers; served in the South African War (mentioned in despatches); b. 23 Nov 1868; d. 11 June 1906.

-

Hubert Victor, Lieutenant, 4th Battery Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers; b. 24 July 1870; m. 19 Feb 1902, Charlotte Fraser (d. 9 Mar 1936), youngest daughter of George Pim Malcolmson of Woodlock, Portlaw, Co. Waterford; d. 15 Aug 1910, leaving issue.

-

Guy Reginald (later of Sydney, Australia), late Lieutenant, Inniskilling Fusiliers; served in the South African War (1899–1902) with the 22nd Rough Riders, and in the Great War (1914–18) with the Australian Expeditionary Force; b. 6 Nov 1876; educated at Rossall; m. 1913, Ethel Spendelow.

-

Dorothea (Dodo) Selina Navarra, m. Oct 1891, Edward Charles Thompson, MP, F.R.C.S.; she d. 3 Aug 1928, leaving two daughters.

-

Amelia (Emy) Charlotte Olivia, m. 23 July 1902, John Willis, second son of Gen. Sir George Willis, GCB.

-

Eleanor (Nell) Harriette Woodrop, m. 12 Sept 1901, Capt. George Peacock, West Indian Regt and Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers; d. 3 Feb 1925, leaving one daughter. He d. 1923.

-

Madeline Frances Edith, d. 20 Jan 1933.

-

Florence Beatrice Hanna, m. 23 July 1902, Capt. Audley Willis, 3rd Battery Hampshire Regiment and 60th King’s Royal Rifles, third son of Gen. Sir George Willis, GCB; with issue, one daughter.

The house at Seskinore was remodelled and extended in 1862 to a design by Boyd & Batt, architects based in Londonderry and Belfast (DB 4, 15 Mar; 1 Oct 1862, pp. 72, 254). It was a fine house, comprising five public rooms, ten bedrooms, staff quarters, and a separate house for the butler.

George adopted the name George Perry-McClintock, presumably out of respect for and in recognition of the inheritance from his great-uncle, George Perry. He had a coat of arms designed, quartering the Perry and McClintock arms (though not formally granted). These arms were displayed on the newly remodelled Seskinore House, above the pediment of the porte-cochère, and also at the Orange Hall in Seskinore village, where they can still be seen today.

The demesne at Seskinore, as depicted in the 1846 map, differs notably from what we see today. It was substantially remodelled by George Perry McClintock, who re-routed the main road and enclosed additional land to enlarge and reshape the demesne into the more familiar layout still visible today (see map, below right).

The original courtyard was extended, and a second courtyard was constructed to accommodate the expanding estate. This included stables, barns, kennels, various estate offices, and a dedicated house for the butler (below left).

The butler's house, which was just at the back of the wallled garden, demolished c.2010.

Tragically Harry Edward McClintock died on the 2nd April 1866 and then the eldest son Beresford died aged 9, on 31 January 1870. George Perry-McClintock made the following petition (c.1873):-

Marcus Gervais By Divine Providence

Archbishop of Armagh Primate of all Ireland

and Metropolitan and Bishop of Clogher

To our beloved in Christ the Reverend

the officiating Minister in the Parish of Donaghavey

and the reverend Robert Vickers Dixon, Doctor in Divinity

Rector of the parish of Clogherney in our Diocese

of Armagh.-

Whereas Major George Perry McClintock,

J.P.D.L. of Seskinore, near Omagh in the County

of Tyrone has presented a Petition to us stating that

the remains of his brother Samuel John McClintock

who died September 1st 1854, and also those

of two of his children, Viz Harry Edward McClintock

who died April 2nd 1866, and Beresford George

Perry McClintock who died January 31, 1870

were interred in the Churchyard of Fintona

in our Diocese of Clogher said remains

having been interred in leaden coffins, and

That Major (McClintock) desires to remove said remains

to the Burial place constructed and set apart

for the use of members of his family in the

Churchyard attached to the Chapel of Ease lately

built at Seskinore, Parish of Clogherney, in our Diocese

of Armagh.

And Praying us to grant him a Faculty

for this purpose.

We Assenting to such Petition hereby grant our licence:

1. To exhume the said Corpses of the said

Samuel John McClintock, Harry Edward

McClintock, and Beresford George Perry

McClintock, if the same can be discerned

from the other corpses therein or near them

inhumed.

Second- To deposit and intomb the same in

the said Burial Place in the Churchyard

attached to the Chapel of Ease at Seskinore

and we order

3. That such exhumation, depositing, and

intombing be conducted, decently and reverently.

Dated +c

(PRONI DIO.4/32C/9/11/5)

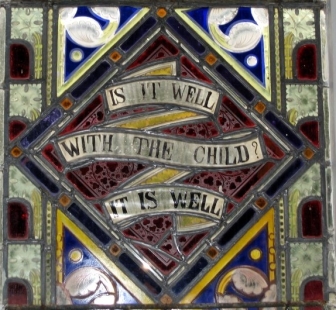

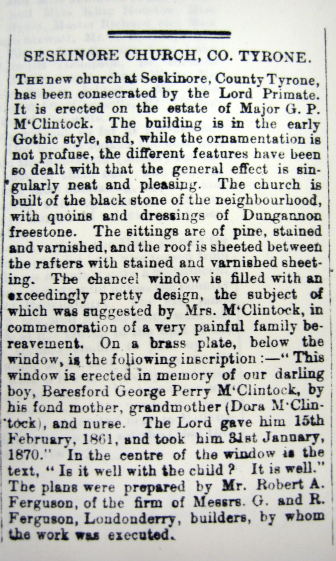

Amelia, Dora, and Ninny (Beresford’s nurse, Jane Knews) commissioned a commemorative stained-glass window (shown below right) for the newly built Chapel of Ease on the estate. The church was consecrated on Tuesday, 9 September 1873, by His Grace Marcus Gervais Beresford, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland.

Beresford with Ninny (Jane Knews) his nurse.

The coat of arms which are currently displayed in the courtyard wall at Seskinore forest, were previously said to have been part of the pediment above the porte-cochère of Seskinore House, in 2019 Sarah Goss was commissioned by Alex Watson to recreate it in lime wood.

Seskinore House, c. 1870's

Perry-McClintock coat of arms, Orange Hall, Seskinore.

A digital depiction of the Perry-McClintock arms as used by George Perry-McClintock. The coats of arms are the work of heraldry expert Eddie Geoghegan (ARALTAS).

4th Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. 1874.

1. Major. (G. P.) McClintock

2. Lieut. C. M. Alexander

3. Capt. C. K. Colhoun

4. Capt. J. Auchinleck

5. Capt. R. S. Hamilton

6. Lieut. H. Alexander

7. Lieut. H. Irvine

8. Lieut. R. Miller

9. Lieut. Col. I. A. Caulfield (Coms Officer)

10. Capt. Deane Mann

11. Major. (Lt. Col) Ellis

12. Lieut. J. B. Thompson

13. Capt. L. Buchanan

14. Lieut. H. French

15. Lieut. Anketell

16. Capt. The Hon. R. O'neil

17. Lieut. I. Stronge

18. Capt. (Bt. Major) Armstrong

19. Capt & Adjt R.C.D. Ellis

20. Surgeon Moore

21. Asst Surgeon Thompson

22. Quarter master Coue?

George Perry-McClintock died on the 26 Dec 1887, his eldest surviving son John (Jack) Knox inherited the estate in tail male,

John (Jack) Knox McClintock, CBE (1921), JP, DL, was born on 8 February 1864. Educated at Cheltenham College and Oxford Military College, he served with distinction in the British Army. He commanded the 4th Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers (Royal Tyrone Fusiliers Militia) from 1881 to 1887 and held the honorary rank of Captain in the Army from 1900. He later commanded the 3rd Inniskilling Fusiliers from 1909 to 1919, was promoted Brevet-Colonel in 1917, and served in the Great War (1914–1918), during which he was mentioned in despatches.

In 1891, he was appointed High Sheriff of County Tyrone. Following his retirement from the army, he became deeply involved in the organisation of the Ulster Special Constabulary in Tyrone and was appointed County Commandant. He also served as Vice-Chairman of Tyrone County Council and as Aide-de-Camp to the Duke of Abercorn during his tenure as Governor of Northern Ireland.

On 27 April 1893, at St Stephen’s Church in Dublin, Jack married Amy Henrietta Frances Eccles, the eldest daughter and co-heiress of John Stuart Eccles, Esq., D.L., of Ecclesville, Fintona, County Tyrone, and Frances Caroline Browne of Aughentaine Castle, Fivemiletown. The Ecclesville Estate, encompassing 9,227 acres, partly bordered the McClintock estate.

Ahead of their marriage, a disentailing deed was executed on 24 April 1893, followed by a marriage settlement on 26 April 1893. The settlement specified that if there were no male heirs from the marriage—or from any future marriage of Jack’s—the Seskinore Estate would pass to a daughter, if born.

The Ecclesville Estate, meanwhile, was entailed in tail male, meaning Amy held a life interest. Should she die without a son, the estate would pass to the eldest son, if any, of her sisters, and so forth according to the entail.

Seskinore entail from the marriage settlement dated 26th April 1893,

Amy and Jack resided at Ecclesville for several years following their marriage, before eventually relocating to Seskinore. A celebration was held on 1 May 1895 to mark Amy’s 21st birthday, suggesting they were still living at Ecclesville at that time. Sometime between 1895 and 1901, the couple made the move to Seskinore, where they are recorded as residing in the 1901 census. However, the census also notes that Jack was in Dover, England, likely engaged in military-related duties.

1901 Census fo Seskinore

|

Surname |

Name |

Age |

Sex |

Relation to head of family |

Religious Profession |

Where born |

|

McClintock |

Amelia [sic] Henrietta |

26 |

Female |

Wife |

CE |

Dublin |

|

McClintock |

Leila |

2 |

Female |

Daughter |

CE |

Dublin |

|

Fowler |

Lizzie |

22 |

Female |

Housemaid |

RC |

Armagh |

|

Murray |

Sarah |

55 |

Female |

Cook |

RC |

Armagh |

|

Charpentier |

Mathilde |

18 |

Female |

Ladies maid |

RC |

Paris |

|

McGovern |

Mary |

23 |

Female |

Kitchen maid |

RC |

Cavan |

|

Cross |

Susan |

37 |

Female |

Nurse |

RC |

Monaghan |

(L-R) J.K McC, Amelia C McC, Guy McC, Amy H McC,

in front, Rose Eccles (sister of Amy McC), Portrush 1896.

A letter written by Augustus McClintock to his sister-in-law Amy, from The Old Hall in Rostrevor—where the McClintocks were holidaying—offers a glimpse into family gossip and also confirms their living arrangements. The letter was most likely written in 1896, as it references Amy’s uncle, Charles Eccles, who died in 1897. This would also place it around the time the photograph above was taken in Portrush, circa 1896.

The Old Hall

Rostrevor

Monday

My Dear Amy

Thanks for sending the bike. Mother is not getting on at all as fast as she ought to her temperature is up every night and she still feels the pain in her chest. I don't know what it can be. old Vesy says that he thinks her lung better, but I don't believe in him, I hate his rotten jokes, and I am certain he does not understand her, Hubert is now laid up with a sore foot and can hardly get about at all, it is an old hurt, and has turned into a boil and looks very bad. Nell has gone to meet Emy at Portadown and bring her on here, Dodo drops her there on the way to Belfast to see Dentist and comes here this evening. I am going to Armagh tomorrow to see Harry about my life insurance, I am coming back the same evening, as I think I am going to Portrush on Thursday, I will go via Derry, as I am going to see King on my way. I hope the hounds are giving every satisfaction, I have not seen your letter as Nell took it to read in the train.

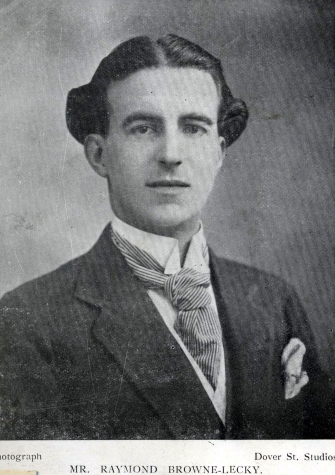

The shooting must have been good at Dassy's I suppose the rain spoiled it a good deal. Your Uncle Charles walks past every day with his wife, I never saw anyone so changed in appearance since the last time I saw him when they were living in Kingstown, he looks so old and sour looking now. Mrs B Lecky is very kind sending nearly every day to ask for mother she and Missy were here yesterday, I did not see them. Mr B Lecky had his shoot the other day and managed to get 25 pheasants I believe he was greatly annoyed about it. Funny enough. Nell and I went to church yesterday it was dull enough. Young Raymond was there his hands covered with large diamond rings, big button hole, specs with gold chain, gold chain to hold his Tyrolean hat on with, altogether a terrible sight, I think its a pity of the boy. I am not enjoying my stay here, There is absolutely nothing to do and it has been raining nearly the whole time. I had no idea Rostrevor was such a wee dog hole, I expected it to be a fashionable health resort, but it certainly is warm and the house very nice only leaking in 3 places. You & dear Jack must come down. It will be much better when poor Ma can get up, but she cant as long as her temperature keeps so high at night.

Rose sent one of the cuffs for my smoking coat, its very nice, I sent the pattern for the collar, it will be a smartish garment when it is finished. When are you thinking of getting over to Seskinore=I will not get my company yet both the steps have been absorbed which is much better than bringing in an outsider, so probably when the next step goes I will have the required service and will then get it all right. I was in Newry Saturday with Florence shopping its not much of a town

Low church

High steeple

Dirty streets

Proud people

That’s Newry

The length of this letter has overcome me.

With much kind love from the Rostrevor division of the family to those at Ecclesville

Augustus

Rejoicings at Ecclesville

Coming of Age of Mrs M'Clintock

On Wednesday the beautiful grounds sur-

rounding Ecclesville were the scene of much

animation on the occasion of the celebration of

the coming of age of the popular owner. The

first part of the celebration took the form of a

dinner to the tenantry on the estate and to the

Seskinore tenants, and for this upwards of 400

invitations had been issued. The purveying

had been placed in the hands of Messrs. John-

stone & Son, Criterion Restaurant, Derry, and

that firm carried throughtheir part of the pro-

ceedings to the entire satisfaction of the givers,

Captain and Mrs. M'Clintock, and equally to

the satisfaction of the guests. To provide ac-

comodation for the large number of guests, all

the p.ublic rooms of the house, including the

dining-room, library, &c., were utilised, and

the 400 guests present were enabled to dine in

comfort. In the dining-room covers for over

80 guests were laid, and here shortly after four

o'clock Captain M'Clintock took the chair.

Accompanying him were Mrs. M'Clintock. Mr.

H. M'Clintock. Mr.--- M'Clintock, the Misses

M'Clintocks, Dr. and Mrs. Edward Thompson,

Mrs. Duncan, and Mrs. Donaldson

The Tyrone Free Press, May 4, 1895.

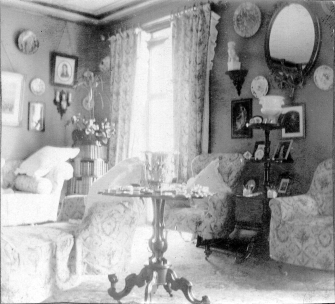

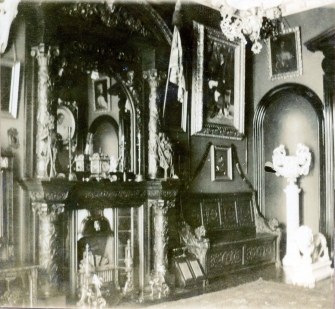

Photographs from the 1890s offer a rare glimpse into the interior of Seskinore House, depicting the hall and drawing room in rich detail. In the image of the hall, a portrait of Jack is seen to the right of the fireplace, while a mirror above the mantel reflects a portrait of Amy, housed in an ornate Florentine frame. The painting is attributed to Costa—most likely John da Costa, the renowned portraitist of the period.

*Listed in 'Copy inventory and valuation by Gallows of Oxford Street, London, in respect of land at Seskinore Lodge, for Colonel J.K. McClintock. [Dec. 1914]'. PRONI D1716/19

An 'A' Special Constabulary mobile platoon, infront of Seskinore house.

Jack was an avid hunter and succeeded his father as Master of the Tyrone Hunt in 1886, renaming it The Seskinore Hunt. He held this position until 1904, when Mr. King Houston of Omagh took over. The hunt was suspended in 1915 due to the First World War but was revived in 1922, with Jack once again serving as Master. He remained in that role until his death in 1936.

THE SESKINORE HARRIERS were first established as

a private pack in 1860 and were the property of the

McClintock family until 1904, during which time

the kennels were at Seskinore. They then bacame a

subscription pack, but hunting was suspended from

1915-1922 owing to the Great War.

Distinctive Collar:- Green Velvet; Hunt Buttons,

(Hare Galloping); Evening;- Dark Green Coat, Green

Velvet Collar, Crimson Waistcoat; Evening Buttons,

(Hare, full face).

MINIMUM SUBSCRIPTION, - - £3

CAP, 1/-,

Seskinore Hunt Button (Hare Galloping).

Amy (née Eccles) McClintock with two of her McClintock sisters-in-law.

Left to right: Amelia (Emy) Alexander, married to George Perry-McClintock; Amy Eccles, married to John Knox McClintock; and Dorothea (Dora) Knox, married to Samuel McClintock. (Photograph c.1895)

Colonel John Knox McClintock & Amy (nee Eccles) McClintock

On 21 July 1898, in Dublin, Amy gave birth to her first and only child, Amelia Isobel Eccles McClintock. She was affectionately known as Leila and appears to have enjoyed a happy childhood, growing up in the family home and embracing the rural lifestyle and pastimes typical of the Irish landed gentry.

As a child, Leila created her own garden near the house. Her playful sense of humour is captured in a small detail: a sign she placed at the entrance gate to her secret garden that simply read,

"Please Knock."

In a letter dated 13th January 1903, John K McClintock, asked for legal clarification on the entail:-

13th January 1903.

Omagh

Co. Tyrone.

Ecclesville Estate.

Dear Sir,

In reply to your letter of 10th inst.

The Ecclesville Estate goes as follows:-

If Mrs McClintock dies without a son the

Estate goes to Miss Eccles (Rose) if alive, for her

Life, if she dies without a son it will then go to

Mrs Stoney (Dosie) if alive for life. If she dies

without a son it will go to the eldest son

(if any) of the late Charles Edward Eccles.

If he has died without a son it will go to

Robert Gilbert Eccles (Grand uncle) if alive for his life,

And after his death to his eldest son.

Failing all this it will go in thirds to the

Daughters of Mrs McClintock, Miss Eccles and

Mrs Stoney. If Miss Eccles should die without

children, then one half to the daughters of

Mrs McClintock and one half to the daughters

Of Mrs Stoney. Under settlement of the

Ecclesville Estate executed upon your marriage

in case Mrs McClintock dies without a son

your daughter will only receive £3,000 out of the

entire estate.

Seskinore Estate.

Upon your death the estate goes to your

Daughter provided there is no son.

Yours faithfully,

King Houston

Major J.K McClintock

Seskinore.

Little is known about Leila McClintock’s early life. A handful of photographs—rescued from an album during the sale of Seskinore House—offer brief glimpses, but little else survives in the written record. Around 1912, a number of newspaper clippings describe the annual concerts held at Fintona Town Hall and at Ecclesville, hosted by Raymond Browne-Lecky, Amy’s cousin. Amy regularly performed at these events, often duetting with Raymond; yet, Leila is never mentioned in connection with them.

During a visit to Seskinore in 2005, it became clear that questions about Leila’s life—and particularly about Amy—were met with discomfort. When we asked locals about Amy’s life or her burial place, there was a telling silence, and the expressions on their faces suggested they knew more than they were willing to share. No details were forthcoming—until, later that evening, at a welcome party held in the local school, a few villagers approached and quietly shared the story.

According to their account, sometime around 1916, Colonel McClintock—by then too old for active front-line duty—was commanding the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers in Londonderry. It came to his attention that Amy was involved in an affair with a man from Omagh. Acting swiftly, the Colonel returned home unexpectedly and caught the pair in flagrante. Enraged, he is said to have chased the naked man from the house, brandishing a horsewhip.

This dramatic episode was later corroborated by Rosalie McClintock (née Orr), daughter of W. E. Orr, Clerk of the Crown and Peace, and a close friend of the Colonel. Rosalie recalled that the man in question was George Fleming, son of Dr. Fleming of Campsie House in Omagh. She claimed the Colonel had threatened to shoot Fleming on the spot—and that he would have been justified in doing so.

Following the scandal, Amy was effectively banished from the McClintock family circle. She was excluded from all family events and compelled to leave Ireland, settling near her sister in Gloucestershire. It is said she never returned to Ireland during her husband’s lifetime.

This version of events aligns with archival records: on 27 November 1917, Leila is listed as enrolling at RFC Rendcomb in Gloucestershire, suggesting that both mother and daughter were living in the area by that time.

WOMEN'S ROYAL AIR FORCE

CERTIFICATE OF DISCHARGE

ON DEMOBILIZATION.

(MEMBER)

No: 2465

Name: McClintock Leila

Rank: Member

Air Force Trade: M.T. Driver (Crossley)

Enrolled on. 27/11/17 at 21st Wing, at Rendcomb.

Description

Age: 20

Height: 5'9"

Build: Slight

Eyes: Grey

Hair: Fair

Her work during the time she has been in the Force has been carried out in a highly satisfactory and thoroughly exemplary manner.

Her personal character has been Excellent.

Date 17 May 1919, Rendcomb.

Leila with her father.

Leila in uniform behind the wheel of a Crossley, circa 1917, at RFC Rendcomb, Gloucestershire.

Amy’s sister Dosie was living in Gloucestershire at the time, and it was there that Amy and Leila settled following the breakdown of Amy’s marriage. Several letters held in the McClintock archives at PRONI (D1711/2) reveal just how deeply strained the relationship between Amy and Jack had become. The rift never healed, and the lasting fallout significantly affected the dynamics of the family. So deep was the divide that even after Jack’s death in 1936, Amy did not attend his funeral in person but sent a representative in her place. It’s possible that, had relations not been so acrimonious, the management of the estate might have taken a different path—one perhaps better equipped to weather the turbulent years that lay ahead.

FROM

LT.-Col. H. G. S. ALEXANDER, F.S.I.

Telegrams- “CARRICKMORE.”

Station-

CARRICKMORE HOUSE

CARRICKMORE

Co. TYRONE

1st day of Oct 1923.

My dear Jack.

I had a letter from Mrs McClintock in which she asks me

to tell you she would like the following things sent to

Rose Delmege Manor House., Cricklade, Wiltshire.

As the old Delmeges would buy them from her & they

are going to come to see them when they arrive

sometime this month, as the old pair are going

abroad by beginning of Nov. next.

- Her Grand Mother’s picture.

- The Best of the Claud pictures.

- All Ecclesville Silver but not the cup from servants gantrie.

Rose will pay for packing, insurance & carriage.

She says “if she gets the above sold the money will

“get her out of debt & helps to furnish Leilas flat

“which is only like a labourers room”

So it is better that you get a man to

pack all up securely, have them insures &

sent off by Belfast & Liverpool, carriage forward.

The man to insure lives next door to White Hart at

the corner. Mrs McC is moving into another cottage

called Holm Dene next month & Dosie is going

to her home, Milton Lodge, Fairford, Gloucestershire.

Yours affectionately

Henry Alexander

Send me all

c/o Dickey

The agent for the Ecclesville Estate was Lt-Col. Henry George Samuel Alexander (1848–1931) of Carrickmore House, County Tyrone. He was Jack McClintock’s maternal uncle—his mother’s brother.

Leila with a friend (possibly a family member).

Leila met Lieutenant Cecil Rhodes Field, who served in the ASC (Air Surveillance & Control) within the RFC and later the RAF. They were married on 1 January 1920 at the Register Office in Hanover Square, London. However, the marriage was short-lived, and they divorced in 1927.

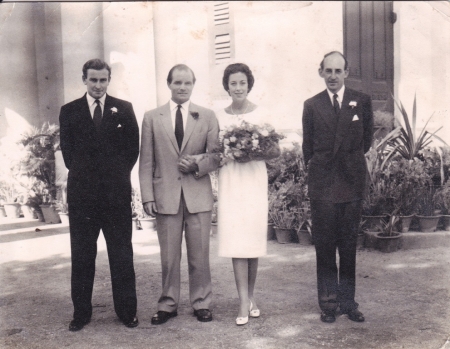

Leila later met Captain Wilfred Heyman Joynson Wreford—known as Tony Joynson-Wreford—a former RAF officer with a lifelong passion for aviation. They married on 30 August 1932 at the Registry Office in Fulham, London. The marriage was witnessed by her mother, Amy McClintock.

Captain W. H. (Tony) Joynson-Wreford

Wilfred Heyman Joynson Wreford was born on 30 July 1896 at 18 Belsize Grove, London. His birth certificate records his name as Wilfred Samuel Joynson Wreford, though the middle name Samuel was later replaced with Heyman. He was the son of Dr. Heyman Wreford, MRCS, LRCP, and Catherine Hannah Guerrier. Wilfred had two older siblings: a brother, Bertran William Heyman Wreford, and a sister, Christabel Emma Catherine Wreford.

Heyman Wreford initially worked in the Wreford family business, a gentlemen’s drapery firm based in Exeter. Remarkably, at the age of forty, he chose to retrain as a medical student in London. In 1892, he married Catherine Hannah Guerrier, daughter of Henry John Guerrier, a corn merchant. Catherine’s mother, Emma, was the daughter of William Joynson, owner of the prominent Joynson's papermill in St Mary Cray, Kent.

After spending a period in Brighton, the Wreford family eventually settled in Exeter, where they lived at “The Firs,” Denmark Road.

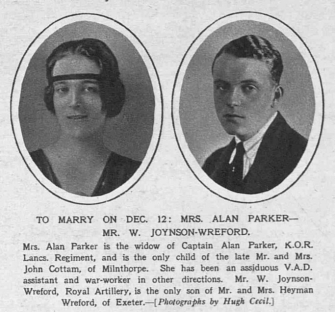

The Sketch, 11 Dec 1918.

Tony Joynson-Wreford was married three times. His first marriage was to Frances Agnes Parker (see above), the widow of Captain Alan Foggett Parker. They were married at the Chapel Royal, Savoy, London, on 12 December 1918. Frances had a daughter, also named Frances, from her previous marriage.

In 1923, Tony began an affair with Olive Fletcher (née Trainor), the wife of Henry Keddey Fletcher, a director of Fletcher, Son and Fearnall, marine engineers of Union Docks, Limehouse, and Tilbury. The affair led to the collapse of both marriages. Olive and Keddey Fletcher divorced; she lost custody of their two daughters, Patricia and Barbara, but was granted a substantial annuity. Tony’s divorce from Frances was finalized on 1 February 1926, and he married Olive shortly after, on 10 March 1926, at the British Consulate in Paris.

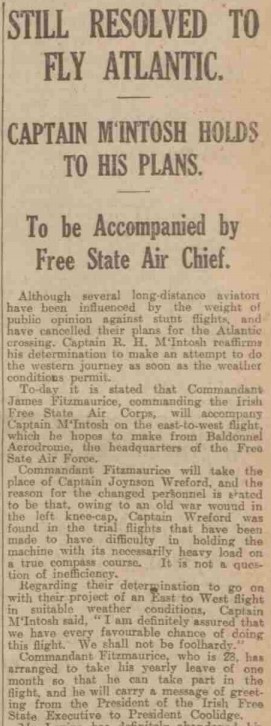

In September 1927, Tony Joynson-Wreford co-financed an ambitious attempt to fly from Baldonnel, Ireland, to America in a Fokker F.VIIa monoplane named Princess Xenia. Tony was originally intended to serve as navigator on the flight, which was to be piloted by Captain Robert MacIntosh, the aircraft’s owner. However, due to the recurrence of an old leg injury, Tony was forced to withdraw from the flight. He was replaced by Commandant James Fitzmaurice.

The main financier of the venture was William Bateman Leeds, who named the aircraft in honour of his Russian wife, Princess Xenia Georgievna. The Princess Xenia's arrival at Baldonnel was captured on film by Pathé News, and footage from the event still survives.

Evening Telegraph - Monday 12 September 1927

A heavily pregnant Olive Joynson-Wreford standing beside her husband, Tony Joynson-Wreford, next to the Princess Xenia at Baldonnel Aerodrome, September 1927.

A few months after the failed Princess Xenia transatlantic attempt, Tony Joynson-Wreford accompanied Captain W.G.R. Hinchcliffe, DFC, on an inspection of Baldonnel Aerodrome. Reports at the time suggested they were considering it as the headquarters for a new transatlantic flight effort. Just two weeks later, at 8:35 a.m. on 13 March 1928, Captain Hinchcliffe departed in the Endeavour, a Stinson SM-1 Detroiter monoplane. His supposed co-pilot was listed as "Gordon Sinclair," but it was later revealed to be the Hon. Elsie Mackay, daughter of the 1st Earl of Inchcape, who had disguised her identity to make the historic flight.

The aircraft was spotted several times en route but tragically disappeared over the Atlantic. Eight months later, a piece of its undercarriage washed ashore on the west coast of Ireland—grim confirmation of its fate.

In a poignant footnote to this story, Princess Xenia herself later became close friends with Lady Rosemary Mackay, the grand-niece of Elsie Mackay. She even served as a bridesmaid at Lady Rosemary’s wedding—an unexpected link between two women connected by aviation ambition and personal tragedy.

A VISIT TO BALDONNEL

Captain Hinchcliffe and Captain Joynson-Wreford were at Baldonnel aerodrome about a fortnight ago, and,. although no absolute definite arrangements were made, it was understood that he would make the aerodrome the headquarters for his Transatlantic attempt.

(The Irish Times Wednesday March 14, 1928)

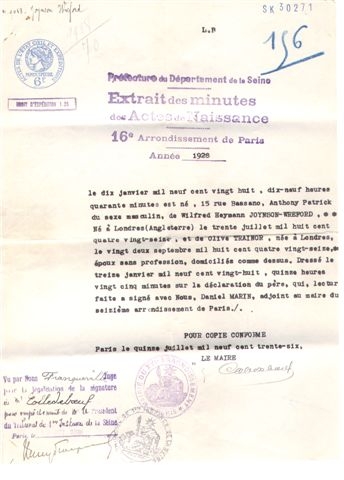

The following January, Tony and Olive were in the south of France, with Olive nearing the end of her pregnancy. Determined to return to England to give birth, Olive made her way north but became unwell after eating oysters in Paris. She went into premature labour and, on 10 January 1928, gave birth to a healthy son in a hotel on Rue de Bassano. The baby was named Anthony Patrick Joynson-Wreford—known as Pat.

Shortly after Pat's birth, the marriage between Olive and Tony began to unravel. By October of that year, Olive left England with her infant son, bound for America. According to Pat, his mother told him that his father had left after his birth and never returned. This narrative shaped Pat’s early view of Tony as distant and uncaring—an impression he would later revise after speaking with people in Seskinore who had known his father and reading personal letters preserved in the National Archives.

These letters, submitted during divorce proceedings, revealed a very different picture. Tony wrote candidly about the collapse of his finances and the emotional toll of the previous 14 months—a period marked by the failed Princess Xenia flight and the tragic deaths of Elsie Mackay and Captain Hinchcliffe. They showed a man struggling under immense personal and financial pressure, and they made clear that Tony’s absence may have been more circumstantial than intentional.

Any effort Tony might have made to remain part of his son’s life would have been complicated. In October 1928, Olive and nine-month-old Pat boarded a ship to America, armed with letters of introduction and grand ambitions to make a name for herself in Hollywood. However, on arrival in New York, she was denied entry for not holding an immigration visa. With insufficient funds to return to England, Olive and Pat were deported to the nearest British protectorate—Bermuda.

Olive with Pat in Bermuda. c.1932.

The Honywood Hotels Ltd.

CARTER’S HOTEL,

ALBEMARLE, STREET,

W.1.

c/o G,R, Cran

“A’’

Dear Olive

Your wire arrived yesterday & I answered it. So I presume you have left for Cannes by now. Why you should have addressed it to the Hotel & not to me I rather fail to understand. But I have a very good idea. I have thought things over very seriously since I last saw you & I have come to the conclusion that it is hopeless for you & I to try & continue as we are now. I would have talked to you about it in Paris. But it is useless for you & I to try and argue out anything. I have asked you before & I ask you again now to divorce me.

After all you are young – in fact we both are & I cannot see the point of continuing in a marriage which has turned out so disastrously - I don’t want you to think that I am unfair – you know yourself that the position is hopeless.

The child I promise you will be looked after & naturally I shall be responsible for you up to a certain point. That can be arranged by the lawyer. I know a man in Paris who will do everything quietly. I imagine you would prefer it that way. There is no question of any other woman. Although you invariably think so – it is merely incompatibility of temperament or anything else you like to call it. The last 14 months have not been pleasant & I must work to live. I feel I should be far better alone. I know that this letter will upset you & probably make you furious – so but please read it over several times – very carefully. I am leaving here & I am still uncertain as to where I shall be so will you write to me c/o Cran – I only suggest this as I shall be moving quite a bit & can always get him on the telephone & tell him my address. I am very sorry about everything in many ways. But it is just one of those things that will happen. As a matter of fact you will be far happier away from me & I will definitely give you enough to live on – more I cannot do – as you know the state of my finances at the moment. Everything can be arranged with the lawyer in black & white – Bobbie I will arrange about. At the moment he is with the vet with eczema. I will send you some money this week.

I hope you are both well & I am very sorry that this should have happened. At such a time as I know it is not good for you or the child. But you must admit that it was all discussed long ago. & you refused to do anything until after the birth of the child – after all Olive. When love has ceased to exist it is useless to continue – we have always been great friends. But as husband & wife we are impossible – That much you must admit.

As soon as I hear from you I will get the lawyer to write you a letter & the whole thing can be done in Paris quietly & decently.

I wish I could have talked to you about all this instead of writing. But that as you know was impossible. I feel now that I want to be alone for the rest of my life – I have tried marriage twice & both have failed – so I shall not try again -

Tony

It may all be my fault if it is I am sorry.

T

The Honywood Hotels Ltd.

CARTER’S HOTEL,

ALBEMARLE, STREET,

W.1.

“B’’

Saturday

My dear Olive

I got your letter this morning & wired you at once. As you particularly want it I will do as you wish but I really don’t see the point. I want you anyway if you will to stay away for a month & think things over. I don’t want you to be unkind as I know you are not well. but you must admit that married life as far as we are concerned is rather hopeless. I feel I want to be entirely alone I really have nothing at all to do with any woman. I tell you this only because I feel it far better that you know the truth.

I will send you some money on Monday- I have none today. I hate to appear unkind so don’t misinterpret my letter.

I hope you are both well.

Tony

You little realize how many worries I have at the moment.

T

Thank heavens I have work to keep my mind occupied.

HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

PROBATE, DIVORCE, AND

ADMLIRALTY DIVISION

CHARGE OF ADULTERY WITH FORMER

WIFE

WREFORD, O. V. v. WREFORD, W. H. J.

AND WREFORD (RESPT.).

(Before the RIGHT HON. the PRESIDENT}

In this undefended petition Mrs. Olive

Vivian Wreford, née Trainor, now a sales-

woman in Chicago, prayed for the dissolution

of her marriage with Captain Wilfred Hey-

man Joynson Wreford, a retired Army officer,

on the ground of his adultery with Mrs. Francis

Agnes Joynson Wreford, his former wife. who

was granted a decree absolute for the dissolu-

ion of her marriage with him on February 1,

1926

The marriage which was the subject of the

present petition took place at the British Con

sulate in Paris on March 10, 1926 There was

one child of the marriage, an infant daughter.

The adultery charged was said to have taken

place at a flat in Moreton-terrace. Old

Brompton-road. where the respondent was

alleged to-be living with his former wife.

Mr. C. L. Beddington appeared for the

petitioner. whose evidence on affidavit was

read.

The President. in giving judgement, said

that the petitioner. when she was a married

woman, committed adultery with Captain

Wreford. Her then husband divorced her

and Captain Wreford's wife divorced him. The

present marriage, as might. have been expected,

was a, disastrous failure. The husband, after

professing weariness of the marriage state

generally, left his wife to fend for herself. She

obtained employment, and later she traced her

husband to an address in London and found

him cohabiting with his former wife.

His LORDSHIP pronounced a decree nisi, with

custody of the child, and costs.

Solicitor,--Mr. George R. Gran.

30 Oct 1929

(The child was mistakenly reported as a daughter in the news report)

Tony & Leila Joynson-Wreford.

At 'The Old Barn', Leatherhead, Surrey, on 3rd August 1935 Leila gave birth to a baby girl, they named her Penelope, she would be known as Xenia.

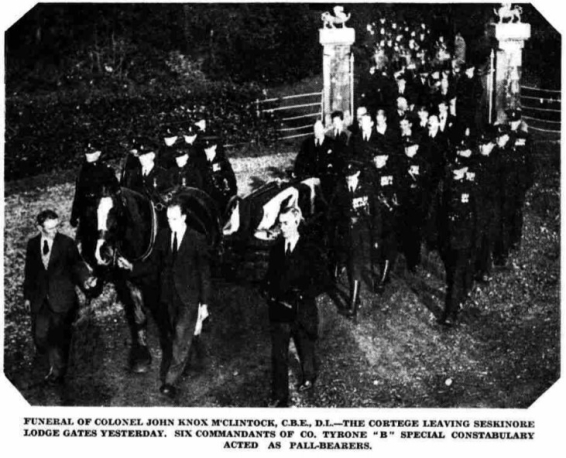

The following October Tony and Leila were holidaying in Switzerland with their baby daughter, when Leila’s father Col. J.K. McClintock, died at his home in Seskinore, on the 24th October 1936. The couple were unable to make it back in time for the funeral, they were represented, by Mr Thomas Frederick Maddocks, solicitor in London.

Col. J. K. McClintock was buried in the McClintock burial ground, next to the Chapel of Ease which had been built on the Seskinore estate.

It appears that, prior to Colonel J.K. McClintock’s death, the Joynson-Wrefords were planning to relocate to Seskinore—likely to assist in managing the estate. During a visit to the stables with his young granddaughter, Colonel McClintock reportedly told one of the workers that his "granddaughter was coming to live at Seskinore."

Following her husband’s passing, Amy McClintock seems to have resolved to return to her childhood home with her family. She placed the following entry in Kelly’s Handbook to the Titled, Landed and Official Classes (1937):

McClintock, Mrs. Amy H., eldest daughter and co-heiress of John Stuart Eccles of Ecclesville, Co. Tyrone; m. 1893, Col. John Knox McClintock, C.B.E., D.L., J.P. (d.1936); 1 daughter: Seskinore, Omagh, Co. Tyrone, N. Ireland. [sic]

Tony and Leila made preparations to move into Seskinore, intending to carry forward the family legacy. But the joy of returning home was tragically short-lived. Just three weeks after their arrival, Leila fell ill with meningitis. Despite every effort, she died four days later, on 30th January 1937, at just 38 years old.

Overcome with grief, Tony reportedly refused to allow her burial. He expressed a wish for her to be embalmed and placed in a glass coffin to remain in the house. The situation became so distressing that the Bishop was asked to intervene. A special dispensation was granted, permitting Leila to be buried in a place deeply personal to her—a small garden she had tended as a child, close to the house.

At her burial, the following tribute was read:

“As a little girl, she made a garden on this site. With her own little hands she planted flowers here, and with childish interest and delight, looked after them. That spot, made sacred by her associations with it when she was a child is now to be sanctified by her abiding presence. Here we shall leave her in hope and peace.”

(Tyrone Constitution, 5th February 1937 — Reproduced courtesy of The Tyrone Constitution.)

Above. Leila's grave in the garden of remembrance, Seskinore. 1937.

Below. c.1939.

Every evening at 6 o’clock, Tony would walk Leila’s dog to the “Mistress’ Garden,” the small sanctuary where she was buried. There, beside her grave, he would sit quietly—sometimes for an hour or more. He never truly recovered from her death, and in the months that followed, his own health began to decline. Those working on the estate observed that he seemed to have "not long for this world."

Over the next three years, Tony spent extended periods in various clinics. Letters he wrote between 1938 and 1940 to Andy McHugh, the gardener at Seskinore, offer intimate glimpses into his health, his grief, and his deep affection for his young daughter, Xenia.

While convalescing at a nursing home in Barnstaple in late 1938, Tony learned that the Chapel of Ease at Seskinore had been damaged on Christmas Eve. His sister, Christabel Gladwell, wrote to Andy McHugh expressing the family's concern upon receiving the news.

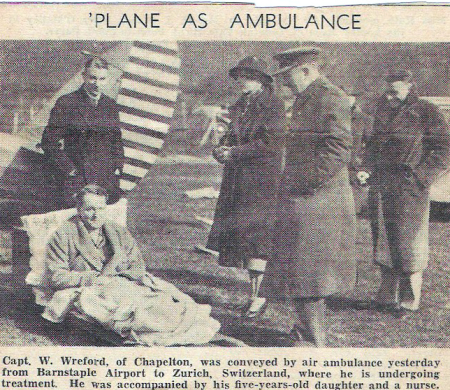

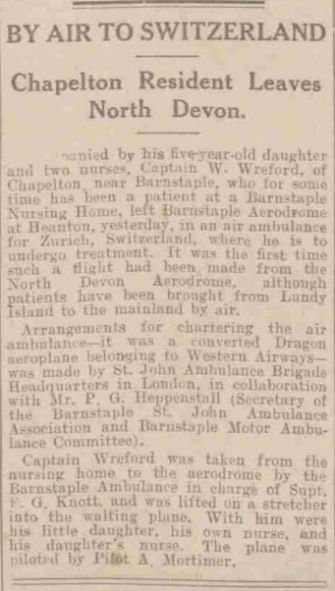

By early 1939, Tony had been diagnosed with tuberculosis. In March of that year, he was transferred by air ambulance from Barnstaple Airport to Zurich, and from there to the Kurhaus in Clavadel, near Davos—a well-known sanatorium for TB patients. He was accompanied by Xenia, his nurse, and Xenia’s own nurse, Helen Hunter (affectionately known as “Nursie”).

'Plane as Ambulance', 23 March 1939.

Devon & Exeter Gazette, Friday 24 March 1939

Tony Joynson-Wreford died on 23rd March 1940 from tuberculosis, while convalescing at the Kurhaus in Clavadel, near Davos, Switzerland. A postcard from 1940 shows the imposing multi-storey Kurhaus building nestled against the Alpine backdrop—serene and remote, yet heavy with the quiet struggle of its patients.

In his will, Tony left a poignant and deeply personal instruction:

"IT IS MY WISH that should my Trustees sell or let Seskinore House they should reserve to all members of my family or of the family of McClintock of which my darling Wife was a member the right in perpetuity to enter the said grounds for the purpose of visiting the grave of my said Wife and to keep-up the Garden of Remembrance wherein she is buried. IT IS MY WISH that my body should be cremated and that my ashes should be scattered in the said Garden of Remembrance at Seskinore."

Local residents remember his ashes being returned from Switzerland during the war, though the conflict delayed the final act of remembrance. They were placed in the Chapel of Ease at Seskinore until the war's end, after which they were interred beside Leila’s grave in the garden she had once tended as a child. A simple memorial stone was placed next to hers, marking their final reunion in the peaceful grounds of the estate.

Mid-Ulster Mail - Saturday 30 March 1940

DEATH OF CAPTAIN JOYNSON WREFORD, SESKINORE.

Intimation has been received in Omagh of the death, which took place in Switzerland. Captain Joynson Wreford, of Seskinore. County Tyrone. Captain Wreford was a son-in-law of the late Colonel .J. K. McClintock. C.B.E., D.L., Seskinore. The late Captain Wreford married the only daughter and heir of Colonel McClintock. His wife died some time ago. His health has been impaired owing to injuries in the Great War. He is survived by a daughter of tender years.

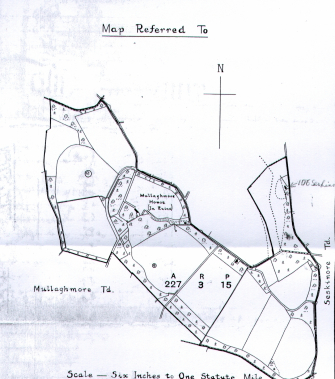

Shortly before his death he sold part of the Mullaghmore estate (below) containing 227 acres, 3 roods and 15 perches to the Ministry of agriculture.

Tony Joynson-Wreford’s Will and the Fate of Seskinore House

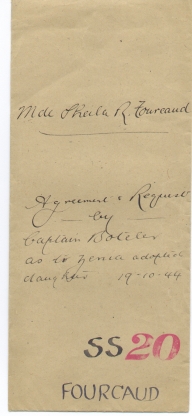

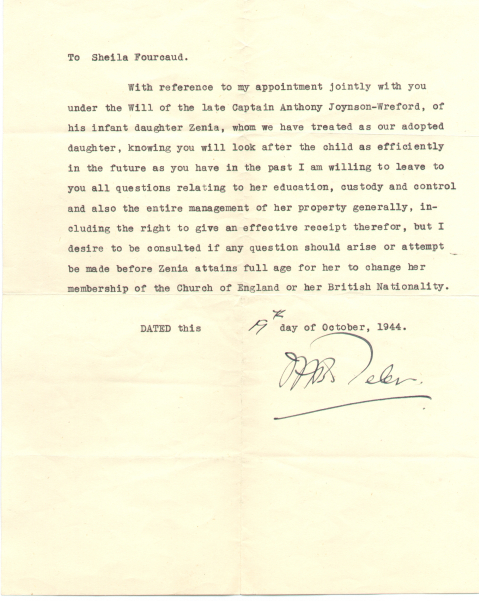

Tony Joynson-Wreford’s will, signed on 18 March 1939, laid out careful provisions for the guardianship and financial security of his young daughter, Xenia. With the threat of World War II looming, his chief concern was her stability in an uncertain future. Originally, he appointed Capt. Anthony C. S. Delmege—Leila’s cousin—and Lady Marjorie Edith Hare as her guardians. However, just one week before his death, on 16 March 1940, he added a codicil to the will revoking that appointment.

Instead, Tony named his close friend Lt-Cdr. John H. T. Boteler and Boteler’s wife Sheila (née Hooper) as Xenia’s guardians. Given Tony’s personal losses in the First World War, including his brother Bertran, he likely feared that Capt. Delmege, an active serviceman, might not survive the new conflict.

The will also established a trust to support Xenia’s upbringing and education until she reached the age of 21. To enable this, Tony granted the trustees authority to sell Seskinore House if necessary.

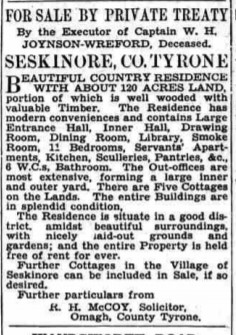

That sale took place in 1941. Seskinore House, along with 115 acres, 1 rood, and 19½ perches, was sold to the Ministry of Agriculture. Importantly, the sale excluded the Garden of Remembrance where Leila was buried, which was legally preserved along with rights of access for members of the McClintock family.

Although the Ministry acquired the estate, they ultimately found no use for the grand residence. In time, the house fell into disuse and disrepair, and by 1952 it was demolished—its final days chronicled in a report by the Belfast Telegraph. Thus ended the era of the McClintock family seat at Seskinore.

Belfast News Letter

Wednesday 10th of July 1940

The End of Seskinore House and Amy McClintock’s Final Years

In 1952, the Belfast Telegraph published a stark headline:

“The end of a house that nobody wanted. 30-room Ulster mansion to go.”

That year, Seskinore House was demolished, its grandeur reduced to rubble. Only the courtyard and outbuildings survived—quiet remnants of a once-bustling estate.

After the sale of the house, Xenia’s grandmother, Amy McClintock, relocated to Molstyn, on Orestan Lane in Effingham, Surrey. She was supported in her later years by family nearby, including her niece Rose (daughter of Amy’s sister Dosie) and Rose’s husband, William Frank Sugden.

Amy passed away on 4 April 1942. She was buried in a modest grave at St. Lawrence Churchyard in Effingham. Eighteen years later, in 1960, her sister Dosie was laid to rest alongside her.

IN LOVING MEMORY OF

AMY HENRIETTA MCCLINTOCK

WHO PASSED AWAY APRIL 4TH 1942

AND OF HER SISTER

ANNA THEODOSIA HESTER STONEY

WHO WENT TO HER REST JULY 8TH 1960

LIFE IS ETERNAL AND LOVE IMMORTAL

Guardianship, Secrets, and Sheila’s Marriage

On Xenia’s ninth birthday, 3rd August 1944, Sheila Boteler married Colonel Pierre Fourcaud—a significant figure in the French Resistance. According to published records, Fourcaud had escaped captivity in Chambéry just the day before, having been imprisoned there since 19 May 1944. Sheila and Pierre are said to have met during the war while Sheila was serving as a driver for the Free French.

Sheila and her then-husband, Lt-Cdr. John H. T. Boteler, had been appointed as Xenia’s guardians in March 1940, a week before the death of her father, Tony Joynson-Wreford. In later years, however, Xenia discovered inconsistencies in the story she had been told. Sheila had claimed that she and John barely knew Tony, saying only that they had met him at the Kurhaus in Davos, Switzerland, where he had asked them—within a week—to take responsibility for his daughter.

This version of events was later proven false. Tony and John Boteler had in fact been long-time friends. The Botelers had visited Seskinore and even spent Christmas of 1937 with Tony and Xenia. Letters from Tony to the Seskinore gardener, Andy McHugh, mention Sheila on several occasions in the months leading up to Tony’s death—establishing clearly that she and Tony had a meaningful and ongoing relationship.

Rosalie McClintock recalled Sheila vividly from a cocktail party at Hampstead Hall during that Christmas season. "Sheila was very glamorous," she said. "She wore a leopard skin jacket which was very striking—she was very social."

These impressions were reinforced by correspondence preserved by Andy McHugh, later passed on to his grandson, Iggy McGovern. In 2005, Iggy and his aunt Cecilia welcomed visitors to Seskinore village to share memories and the letters. Cecilia, who had worked as a young girl for Captain Wreford, remembered him with great affection:

“A lovely man, a kinder man you could not wish to meet.”

Meeting Pat, Tony's son, stirred deep emotion. Cecilia said he strongly resembled his father, adding with a smile:

"Only his father was better looking."

Cecilia passed away in December 2006, leaving behind a heartfelt testament to the enduring memory of Tony Joynson-Wreford.

Xenia and Cecilia McHugh (Sep 2005).

Family Ties and Silences

Xenia’s childhood, already marked by profound loss and displacement, included rare but significant encounters with her extended family. She recalls being visited at school on a couple of occasions by her great-aunt, Anna Theodosia Hester Stoney (née Eccles), known in the family as “Aunt Dosie.” Though the meetings are vague in her memory, Xenia clearly remembers being mortified—called out of class to meet a stern, unfamiliar figure. “She looked like Queen Mary,” Xenia later said, “with a stern face, dressed in black.”

One day, a letter arrived for her at school. The note urged her to speak up and say she was unhappy living with Sheila, insisting she should be with her real family. Troubled and unsure what to do, Xenia gave the letter to Sheila. After that, the visits and letters stopped altogether.

Not long afterward, when she was ten, her trusted nurse Helen Hunter—whom she had known since Switzerland—was quietly dismissed. Xenia was then sent away to Beaufront boarding school. This marked the beginning of a peripatetic education: finishing schools in Paris, Switzerland, and London followed, but the sense of emotional exile seemed only to deepen.

Sheila Boteler with Xenia and Helen 'Nursie' Hunter.

Above. Photographs of Xenia, taken possibly in Northern Ireland.

Below. with her cousin Celeste Ray at the stables in Seskinore, c.1938.

Unspoken Connections

On 2nd October 1954, Xenia served as a bridesmaid at the wedding of her close friend Susan Richards, who married Terence Lowry Rowland Hill. A photograph from the day shows Xenia standing beside her cousin Terence—though at the time, she had no idea of the family bond they shared. She attended the wedding with Sheila and Sheila’s mother, Poppy. What Xenia did not realise then was that the groom, Terence, was her second cousin once removed: both he and Xenia were great-great-grandchildren of Rev. Samuel Alexander of Termon and his wife Charlotte Frances Beresford, daughter of Rev. Charles Cobbe Beresford.

Although the familial connection was known to others present—including Sheila—it was never shared with Xenia. Julia Chessun, daughter of Celeste Ray, later recalled that many McClintock and Alexander relatives attended the wedding and that there had been conversation afterward among the family about Xenia's identity. Yet, despite being surrounded by maternal relatives, Xenia remained unaware of who they were and what they represented in her life story.

It would be over 50 years before she uncovered the truth—a poignant reminder of how near she had come to reconnecting with her mother's lineage, and how that opportunity, at the time, quietly slipped past.

In 1958, during a journey to India with her guardian Sheila, Xenia’s life took a decisive turn. On that trip she met Gordon “Glyn” Lindsay Lewis, a Welsh tea planter who was on his way back to India after a visit home. Their meeting blossomed quickly into love, and just three weeks later, as Xenia prepared to return to England, Glyn proposed.

Sheila, however, strongly opposed the relationship. She had imagined a very different path for Xenia—one that certainly didn’t include marrying a tea planter and living in India. Despite her efforts to prevent it, Sheila's disapproval only strengthened Xenia’s resolve. She was determined to follow her heart.

With quiet support from Poppy, Sheila’s mother, Xenia was secretly given the means to return to India—along with some very practical advice. Poppy told her to "buy a wedding dress, or if things weren’t as she hoped, to use the money to come home."

Xenia chose love. Her journey back to India marked the beginning of a new chapter, one defined by her own choices rather than those made for her.

Glyn and Xenia. Taken onboard the boat to India, 1958.

Xenia and Glyn were married on 14 April 1959 in Bangalore, South India. Their marriage was a happy one, rooted in deep affection and shared adventures. Over the next several years, their family grew with the births of David (1960), Sharon (1963), and Michael (1965). After eight years in India, Glyn sought a fresh start, accepting a role as a Cane Inspector at Inkerman Mill in Home Hill, North Queensland, Australia. Xenia and the children joined him there in 1967. In 1972, they moved again—this time to Pioneer Mill in Ayr, where Glyn became the mill manager. The family lived in the house provided with the position.

Tragedy struck in 1982 when Glyn died suddenly of a massive heart attack. He was just 49. The loss was devastating—not only emotionally, but practically too: their home was tied to Glyn’s job and there was no pension to support Xenia or the children.

At just 48, Xenia was left to start over. Though returning to Sheila in England was an option, it came with strings—she knew it would mean enduring constant reminders of how life “should have gone.” Instead, she chose independence.

Xenia found her footing in a series of jobs, first running a coffee shop, then working in a travel agency, and later serving in the office of a State Senator. After retirement, still full of curiosity and energy, she enrolled at university to study Japanese and French culture. She also harbored a quiet hope of reconnecting with her long-lost school friend Juliet, and registered on Friends Reunited in the hope that Juliet would find her.

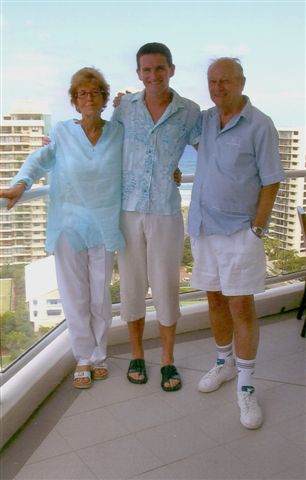

Xenia with her family, David, Sharon and Michael.

It was around this time that aviation researcher David Lang uncovered archival British Pathé newsreel footage of the 1927 transatlantic flight attempt from Baldonnel Aerodrome in Ireland. The footage featured Captain R.H. Macintosh, whose aviation career was well recorded. However, the identity and background of the co-pilot, Captain Joynson-Wreford, remained a mystery.

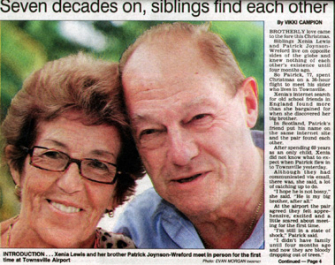

Determined to learn more, Lang posted an inquiry online seeking any information about Captain Joynson-Wreford. His post was eventually answered by Patrick (Pat) Joynson-Wreford, the son of Tony Joynson-Wreford from his earlier marriage to Olive Fletcher (née Trainor). This connection opened the door to a wealth of personal and family insights, helping to fill in long-missing pieces of Tony’s life story.

Patrick Joynson-Wreford, aka Pat Trevor.

Pat had no memory of his father. At the time of his parents’ marriage in 1926, Tony Joynson-Wreford and Olive Fletcher (née Trainor) were living in France. Olive had planned to return to England to give birth, but fate had other plans. After eating oysters for lunch in Paris, she fell ill and unexpectedly went into labour. She gave birth to a healthy baby boy in their hotel room on Rue de Bassano. The child was named Anthony Patrick Joynson-Wreford, known simply as “Pat.”

Patrick Anthony Joynson-Wreford

The marriage between Tony Joynson-Wreford and Olive Fletcher was short-lived. By October of 1926—the same year they wed—Olive had left for America with their infant son, Pat. She remained there for over a decade, returning to the UK in 1938 as the threat of war loomed.

According to Pat, his mother told him that Tony had died in Switzerland of tuberculosis, but offered little else. Her comments about Tony were consistently bitter and resentful. This bitterness may have stemmed in part from the scandal of their relationship: Olive had been married to Henry Keddey Fletcher, with whom she had two daughters, when she met Tony during a visit to London from Brighton. Their ensuing affair brought both marriages to an end, and Olive and Tony were married in 1926.

Olive with her daughters, Patricia (Pat) and Barbara.

I had known Pat since I was about seven years old—he was a family friend with a captivating presence and a gift for storytelling. His tales about his mysterious family background fascinated me from an early age. Over the years, we often talked about researching his father’s history, a shared curiosity that lingered in the background of our friendship.